Forward

My name is Jerrold McGrath, and I am the Executive Director at the JCCC. In service to increased communication, I will be sharing updates regularly so that we can continue to be in conversation about where the JCCC is going.

The timing of these messages will be based on a Japanese calendar of 72 seasons. This system was adopted in Japan by the 7th–8th centuries, where it was refined to reflect local climate, agriculture, and everyday life, turning the calendar into a practical way of paying attention to subtle environmental changes.

Hopefully, this structure will let us think about what small, local changes are underway here at the JCCC and to share them in ways that encourage us to pay attention to the living world rather than just the calendar.

Fuyu (Dec - Feb)

Fish Emerge from the Ice | 魚上氷

(February 14 – 18)

This micro-season marks the moment when ice begins to break and fish become visible again. They were there all winter but covered by ice. As conditions shift, what was present becomes easier to see.

On Sunday, February 15, we hosted a conversation about the future of the JCCC. I outlined the changes underway and the reasons for them. We addressed some rumours and I made explicit our direction going forward. We will be releasing a summary of the points raised on that day in the coming weeks. Today’s message will only look at one aspect of that conversation.

Some people were energized. Others were concerned. Both responses are legitimate.

However, one issue surfaced repeatedly - directly and indirectly - and without greater clarity it will be difficult for us to move forward together.

As an organization and community, we need to determine how post-war arrivals from Japan participate in the long-term stewardship of the JCCC.

Different perspectives were expressed. Some felt that the Centre represents all individuals of Japanese heritage in Canada regardless of when or how they arrived. Others emphasized that the JCCC was created to preserve and tell the stories of those who arrived pre-war and their descendants, and that this founding history must remain central. Still others were open but uncertain about what expanded stewardship would mean in practice.

These are not trivial distinctions. They reflect different understandings of inheritance, responsibility, and belonging.

Our current strategy prioritizes attracting younger Nikkei and engaging households shaped by more recent migration. This direction is based on the belief that the Centre must reflect the full composition of the Nikkei community as it exists today. That includes descendants of pre-war settlers and post-war rebuilders, as well as first-generation immigrants, transnational families, and their Canadian-born children.

Recent census data suggests that the Japanese and Japanese-descended population in the Greater Toronto Area is no longer composed primarily of post-war, English-dominant Nikkei. Since the late 1990s, and especially after 2015, Toronto has seen sustained arrivals of first-generation migrants from Japan, international students, working holiday participants, and bilingual families. Across Canada, a substantial portion of those identifying as Japanese ancestry are first-generation immigrants or have at least one parent born in Japan. In Toronto, the community skews younger than the historic West Coast population, with many residents under 40 reporting Japanese as a mother tongue or regularly used home language.

Increasing the visibility of Japanese in our communications reflects this reality. It acknowledges the growth of bilingual households and signals that the Centre is not only a heritage institution for English-dominant descendants but also a living cultural space shaped by ongoing migration.

At the same time, language carries history.

For many Nisei and Sansei, this Centre was built in English because it had to be. After dispossession and internment, language and cultural expression were not neutral choices; they were shaped by pressure to assimilate and survive. English was not simply convenience, it was protection. The JCCC became a space where Japanese Canadians could gather without apology. That history is foundational and remains so.

Using more Japanese in our communications is not about replacing that history. It is about ensuring that those arriving today, and their children, also recognize themselves here. The question is not whether one language displaces another, but how we hold both without diminishing either.

This conversation is not only about language or programming. It is about stewardship. Is stewardship inherited, participatory, demographic, or earned through contribution? In practice, it is likely some combination of these.

What this means operationally is not predetermined. It may involve advisory structures, leadership pathways, programming priorities, language balance, or governance evolution. Those mechanisms require further discussion and reflection.

What remains constant is this:

Japanese Canadian history is foundational to this institution. The experience of internment, dispossession, and rebuilding is the reason this Centre was created. Our responsibility to preserve and activate that history through the Moriyama Nikkei Heritage Centre remains central. Our commitment to belonging in a volatile world remains central. Our belief in friendship through culture remains central.

These commitments are not changing.

Some other things that are not changing (or are not changing in the way people have heard):

- Bazaar is happening on May 2, 2026 and will be very similar to what you are used to with some additions made to draw in families and slightly less emphasis on selling gently used items

- The New Year’s Euchre event happened in 2025, and we support it happening again in 2026 – the big difference is that we will not be providing staff for it (space will continue to be made available for free)

- There will be no changes in terms of access for Seniors or Senior activities – we have had some conversations about access to storage as we are running out but nothing about access to space for these groups

- In the past, discounts for rentals were inconsistent or inherited – some groups received 80% or 100% while some received zero – we are moving to a consistent rate for all community partners and will not be making determinations about which groups are more or less deserving of deeper discounts – we will be introducing more public seating so that community members can come and gather (without payment)

- All of our many clubs continue to receive space for free (as long as club members remain JCCC members and the work supports the community)

What is changing is how we live into our mission in the present.

We are placing greater emphasis on attracting younger community members. We are moving toward a more coherent seasonal programming structure. We are investing in everyday gathering spaces through the café and stage. We are building Kodomo Corner so that children experience this Centre as theirs. We are strengthening facilities and digital systems to support long-term institutional health. You can learn more about these changes at Donate | Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

These shifts are structural responses to demographic and cultural realities. They do not eliminate existing programs or constituencies, but they do rebalance attention toward where the community is growing.

Toronto has changed. Migration patterns have changed. Younger generations build community differently. If the Centre does not feel relevant to them, they will gather elsewhere. In some cases, that is already happening.

The focus on young people and Shin Nikkei is not about replacing Japanese Canadian identity. It is about acknowledging the full composition of the Nikkei community today and ensuring continuity across generations of arrival.

Who shapes the future of this institution? That question cannot be resolved by goodwill alone. It requires clarity about responsibility and participation, and it requires structures that reflect the community as it actually is.

Fish emerging from the ice is not dramatic. It signals that conditions are shifting and that life continues beneath the surface.

The 75 families who mortgaged their homes were not preserving something static. They were building infrastructure for belonging in a country that had failed them. They could not have predicted the demographic realities of 2026, but they built with the future in mind.

Our responsibility is similar: to maintain purpose while adapting form, and to ensure that stewardship remains strong enough to carry both memory and movement.

This season asks us to be clear, not only about whether change is happening, but about how we share responsibility for it.

Bush Warblers Start Singing in the Mountains | 黄鶯睍睆

(February 9 – 13)

Without the voice of the warbler that comes out of the valley, how would we know the arrival of spring?

- Ōe no Chisato

In the traditional calendar, this micro-season marks the first call of the bush warbler (the uguisu). Its song is taken as a sign that spring has begun.

For many people, that sound inspires powerful memories. It calls up plum blossoms, poems, school lessons, an image of Japan that feels stable and familiar. The warbler’s voice is often treated as a symbol of continuity.

But the bird is not in the least bit concerned about continuity. It is beginning again.

Early in the season, the uguisu’s call is uneven. It practices. The famous, clear “ho-ho-ke-kyo” comes with repetition. What we tend to record and replay as the emblem of spring is the refined version. What actually marks the season’s turn is a clumsy first attempt.

In cultural life, it is easy to build programming around what is already recognized and loved. Familiar forms gather people. They reassure us that something has endured. There is value in that. There is also risk.

When nostalgia becomes the centre, we start curating echoes. We privilege the version of culture that feels complete and authenticated by the past. We become caretakers of an image rather than participants in a living practice. Younger voices, hybrid forms, unfinished experiments can feel out of place because they do not yet sound “right.”

The warbler reminds us that the season begins before the song is perfected.

Its call is shaped by this year’s conditions. It marks territory, signals presence, tests possibility. The bird carries inherited patterns, but it uses them in the present moment.

For communities shaped by migration and change, nostalgia can feel protective. But if it becomes our organizing principle, it can quietly fix culture in a single frame. It can imply that authenticity lies behind us rather than among us.

This micro-season invites us to sing old songs into the present and to value rehearsal as much as performance.

The question for us is not whether we can remember the old songs but whether we are willing to let new ones be heard.

East Wind Melts the Ice | 東風解凍

(February 4 – 8)

This micro-season marks the beginning of risshun, the first day of spring in the ancient lunar calendar. At this point, the year is understood to have turned. What follows is thaw, not warmth. The conditions have not improved; the direction has changed.

Setsubun takes place the day before risshun and functions as a threshold ritual. It clears misfortune so the calendar can advance. Following our recent Setsubun gathering, one participant sent us a message remarking that: “It was cathartic. I have had a rough couple of years personally and professionally, so this ritual was such a great and joyous release of misfortune, greatly aided by it being a community effort.” The ritual did not solve anything. It made movement possible.

Historically, risshun mattered because it required action. Agricultural planning shifted. Court calendars adjusted. Poets, farmers, and households recalibrated their rhythms whether or not the ground had softened yet. The year had turned, and people were expected to respond. Waiting for ideal conditions was not an option.

Institutions can freeze too. Over time, routines harden not because they are wrong, but, quite the opposite, because they once worked. Preserving them can feel like care, responsibility, even respect for those who built them. But preservation can also become a way of avoiding the present.

The east wind does not destroy the ice. It changes how it holds. What was solid begins to loosen. Thaw is unstable though, as anyone that tries to navigate the ground after a blizzard can attest.

We are moving forward with changes shaped by a different wind. These changes will not land evenly. Some will experience them as relief, others as loss, others as disruption to forms they have relied on. Younger generations are inheriting political, climatic, and technological volatility they did not create, while also inheriting institutions shaped under very different conditions. The question is not whether the past should be abandoned, but whether long-standing forms can soften enough to respond to the present without breaking those who depend on them.

On February 15, 2026, we will host a gathering to speak plainly about what is changing at the JCCC, why it is changing, and what responsibility we share in shaping what comes next. This will not be consultation theater or a finished plan. It will be a working conversation and one that recognizes that recalibration is necessary, that it carries risk, and that it should not happen behind closed doors.

There will be food. There will be announcements. More importantly, there will be an opportunity to take part in a turning so that those who will one day call the JCCC home are not asked to live with decisions made without consideration of the home they are being asked to live in.

The Hen Begins to Lay Eggs | 鶏始乳

(January 30 – February 3)

This micro-season marks a small but important shift. Niwatori hajimete toya ni tsuku is often translated as “the hen begins to lay eggs.” It refers to a moment when conditions have settled down enough for an effort at something new to be made. It’s not a particularly dramatic moment (except perhaps for the chicken), but a sign that conditions are such that new rhythms can be tried.

This idea seemed to reflect well the patterns witnessed in our recent artist residency at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre for the holiday Setsubun (which coincidentally falls on the last day of this micro-season, February 3).

The residency brought together Nikkei artists with different relationships to Japanese culture in Canada. Some are artists born in Japan and living across both nations. Some are Nikkei artists who have settled here. Some are Japanese Canadians whose connections to culture, language, and community have been shaped by generations of family history, displacement, or long gaps in transmission. These differences were not at the forefront, but they became part of the learning.

Rather than focusing on finished outcomes, the residency emphasized shared process: time in the studio, workshops with new technologies, conversation, experimentation, and reflection. Mentors Michael F. Bergmann, Kasra Goodarznezhad, and Sarah Boo supported the artists by helping hold a space full of questions, new perspectives, while creating a rhythm that allowed trust and curiosity to develop over two months.

The residency took place in the lead-up to Setsubun, a seasonal turning point that marks the shift toward spring. Setsubun is often known for mamemaki, the throwing of beans to mark the end of winter and welcome good fortune. At its core, it is about acknowledging what has accumulated and choosing how to move forward.

That sense of turning mattered. The residency became a place where artists could reflect on where they were coming from, what they were carrying, and what kinds of practices they wanted to continue. The differences between Japanese, Nikkei, and Japanese Canadian experiences did not disappear but they became a shared site of exploration rather than a barrier.

Join us on February 1

Community members are warmly invited to a free, public exhibition of works in progress that were developed during this residency, held as part of our Setsubun celebrations.

Sunday, February 1

From 4:00 pm onward

At the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre

The afternoon will include:

- An open exhibition of residency works

- Mamemaki (bean throwing)

- Ehoumaki (seasonal sushi rolls, enjoyed facing the year’s lucky direction)

This event is free and open to all. We hope you’ll join us to mark the seasonal turning together — through art, shared space, and a bit of ritual.

Ice Thickens on Streams | 水沢腹堅

水沢腹堅 (mizusawa kōken), “ice thickens on streams,” names a brief period from January 25 to 29 within daikan, the season of deep cold. In the Japanese seasonal calendar, it marks the moment when cold has settled enough to carry weight. The surface has already frozen; what changes now is depth. Movement continues beneath, but conditions above begin to matter. This micro-season is not about closure or stagnation. It is about stabilization - the kind that makes new crossings possible.

This is a useful way to think about where the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre is now.

Over the past several years, some community members have raised concerns that the Centre has become less accessible as prices have increased. That concern is real, and it deserves a direct response.

What has changed is not simply price, but structure.

For many years, community rates at the JCCC developed informally. Some groups received very steep discounts, others less so, without a consistent set of criteria guiding those decisions. Over time, access depended less on shared principles and more on historical circumstance. The result was uneven: some groups had long-term access to free or near-free space, while others - often newer or less established - could not access the Centre at all.

Over the past year, the Centre has undertaken a deliberate review of how space is allocated, with Board oversight, to bring greater clarity and consistency to community rates. The intention is not to restrict access, but to stabilize the conditions under which access is possible. When subsidies operate unevenly, space becomes functionally unavailable to many, even if nominal costs appear low.

At the same time, it is important to be clear: the JCCC continues to support a large number of clubs and activities, and that commitment remains unchanged. These include:

- Ayame Kai

- Sakura Kai

- Himawari Buyō-kai

- Karaoke

- Ohana Hula

- Ping Pong

- Wynford Seniors’ Club

- Token Kai

- Getsuyōkai

- Suiyōkai

- Net de Karaoke

- Urara Minbukai

- Nagomikai

- Utagoe

These clubs are one of the ways the Centre functions as a living community space. They are not the limit of participation, but part of a broader ecology of use that we intend to sustain and expand.

We are also developing a café and additional seating areas within the Centre. This is not primarily a revenue project, but shared infrastructure: a place where people can gather without rental fees, applications, or ad hoc negotiations. In a large, publicly accessible facility, this kind of space matters. It allows presence without permission, and reduces the need for the Centre to decide, case by case, who is most deserving of deeper discounts. Rental revenue and generous community donations can then be directed toward sustaining and improving the shared environment itself, rather than being absorbed unevenly through inherited arrangements.

When some groups have access to free or nearly free space indefinitely, the Centre can become less accessible overall. Stabilizing conditions allows other forms of access to grow: clubs, shared events, informal gathering, and moments of collective presence.

At Oshōgatsu kai this year, prefectural associations shared Kobayashi Hall to present their histories and cultures side by side. No one group displaced another. The space held many at once. This is the direction we are moving toward. We are not taking space away, but ensuring the Centre remains capable of holding a growing community together.

Ice thickens not to stop the stream, but to allow new ways of crossing, so that more people can cross, without asking permission, and without falling through.

Butterbur Buds Bloom | 款冬華

January 20–24 marks Butterbur buds bloom (款冬華 / fuki no hana saku), one of the micro-seasons within daikan, the Greater Cold. In Japan, this moment names the appearance of fuki (butterbur) buds pushing up through frozen ground before winter has truly loosened its grip. The ground is still hard. The air still cold.

Fuki has been gathered for centuries, yet the ways people prepare it have changed over time. New techniques, like tempura, a 16th century import to Japan from Portugal, did not replace older practices. They allowed people to keep returning to something they already cared about, adjusting how it was handled as conditions shifted. What mattered was not preserving a single method but keeping the relationship alive.

Bazaar at the JCCC emerged in much the same way - as a response to difficult conditions. For Japanese Canadians, especially in the decades following wartime dispossession, Bazaar met very real needs. It created a place to gather when space was scarce, a way to support one another when resources were limited, and a reason for people to work side by side across families, clubs, and generations. It offered dignity through contribution and belonging through shared effort. For many, it was where community was felt most clearly.

Over time, the conditions that shaped Bazaar have changed. Japanese Canadian communities are no longer defined primarily by material scarcity, but by dispersion, time pressure, and competing demands. Many younger people are navigating precarious work, rising housing costs, climate anxiety, and a sense of cultural distance that is less about survival and more about meaning. They are often looking for forms of participation that fit into complex lives. They want spaces to connect, learn, and contribute without taking on obligations that feel overwhelming or opaque.

What has shifted, then, is not the desire for community but the forms it might take.

Bazaar will happen on May 2, 2026, on the same weekend and in most of the same ways to which you are accustomed. We will be trying some new things and trying to find ways to draw in future stewards of Bazaar and other activities that are central to Japanese Canadian culture. I have heard, second hand, concern and fear that Bazaar might be going away or changed in ways that make it unrecognizable. I don’t know where those stories are coming from, but I want to affirm that Bazaar will remain an important part of our programming year. However, we will continue to talk about what Bazaar does, and for whom, and to make changes in order to test out assumptions about what the Nikkei community needs now and going forward.

Like fuki buds pushing through the snow, these changes will be gradual and exploratory. We want to consider, together, how long-standing practices can continue to matter by adapting to the lives people are living now, so that what has carried community forward in the past can remain a place of gathering in the present.

Pheasants Begin to Call | 雉始雊

January 15–19

Over the past year, it has become clear to me that some of the ways the JCCC has been working are no longer aligned with the conditions we are living in.

At times, we have relied on patterns that once served us well without fully asking whether they still speak to the present. We have repeated familiar forms, returned to established rhythms, and leaned on nostalgia as a stabilizing force. For many, those forms offered continuity and safety. But as the world outside the JCCC becomes more economically precarious, politically polarized, and environmentally uncertain, repetition alone risks turning culture into habit rather than a living response. When that happens, culture can begin to comfort those already at ease while quietly losing relevance for those navigating change, fatigue, or dislocation.

I want to say this plainly: those ways of working were not wrong. They carried the JCCC through difficult periods, held relationships together, and sustained a sense of home that many people depended on. If they are now being questioned, it is not because they failed, but because the conditions they were shaped for no longer fully apply. The questions people bring with them when they come through our doors have changed, and our work must be able to meet those questions honestly.

In the Japanese seasonal calendar, the period from January 15 to 19 is called kiji hajimete naku, or pheasants begin to call. The days grow longer, but the cold remains. The call does not come from comfort or warmth. It comes because remaining silent is no longer possible, even as conditions stay harsh.

That feels like an accurate description of where we are as an institution.

It has become increasingly clear that continuing to do what has worked before, without accounting for present realities, risks mistaking continuity for community. As Executive Director, I am responsible for how we respond to this moment - and for the consequences of not responding. This year, that means choosing reflection over repetition, and orientation over automatic return. Culture matters not because it preserves the past unchanged, but because it helps people make a home in unsettled conditions.

One visible change you will notice is how we shape our programming and matsuri across the year. Rather than extending established formats first and adjusting meaning later, we will begin by outlining a theme for a season, sharing that direction publicly, and then basing each subsequent decision on that direction. Some plans will remain provisional longer than we are used to. Some activities may no longer be a fit or may require significant changes. This approach asks for patience, and it carries risk: uncertainty can be uncomfortable, and not every experiment will land. We are choosing this trade-off deliberately, because waiting for certainty in volatile conditions often means waiting indefinitely.

This also means that some long-standing routines will change shape, pause, or not return at all. That is not a rejection of memory. It is an acknowledgment that care sometimes requires letting go of forms that no longer serve the present as they once did.

Spring 2026 at the JCCC is shaped around the paired ideas of omote and ura: what is visible and what is held privately. Spring in Toronto draws people back into shared spaces such as celebrations, rituals, and public life. At the same time, personal histories, uneven relationships to visibility, and different thresholds for participation remain beneath the surface. Omote and ura describe lived tensions. Privacy is not always freely chosen, and visibility is not equally safe for everyone.

At the JCCC, friendship has never depended on sameness or constant explanation. It has depended on respect for public form - respecting the protocols of the spaces we enter - and private life - respecting different lived experiences. Our Spring programming digs into this more explicitly. One expression of this shift is the move from Haru Matsuri to Hina Matsuri on March 8, creating space to examine ideas of femininity over time, as well as across generations and contexts. Other programs will evolve in their own ways as this orientation unfolds.

As the year continues, each season will offer a different way of paying attention: movement and memory in summer, especially for younger participants; craft and comfort in fall; and renewal and difference in winter. Together, these orientations serve as a guide for making decisions about what we do and how we do it.

I know this way of working may feel disorienting. For some, it may feel like familiar ground is shifting. For others, it may feel overdue but still tentative. There will be moments to speak back, to question, and to disagree. I will be clear about where decisions are open to influence and where they are not, and I will take responsibility for those boundaries.

The cold is not over. There are still constraints, uncertainties, and difficult choices ahead. But we are speaking plainly about where we are, what we are trying to do, and what this work will ask of all of us.

Thank you for staying in relationship with the JCCC as we do this work in real time.

Springs Begin to Thaw | 水泉動

January 10–14 marks Springs begin to thaw (水泉動), one of the micro-seasons within shōkan, the Lesser Cold period. In Japan, as in Canada, January is often bitterly cold. And yet, beneath frozen ground, something has already begun to shift.

Last week in Toronto, winter briefly loosened its grip. Temperatures edged toward the double digits, snow receded (if only partially), and the city entered that familiar in-between moment when nothing looks different (yet), but something is clearly underway.

In the Japanese seasonal calendar, “Springs begin to thaw” names this exact condition. It marks the point when frozen water starts to move again below the surface. The change is quiet and easy to miss, but it is decisive. Once the thaw begins, there is no return to stillness.

We felt a version of this shift at the Centre on January 9, when members of the Toronto Buddhist Church visited and shared freshly-made mochi with our staff. The mochi is traditionally prepared for kagami biraki, the “opening of the mirror”, a New Year ritual that breaks hardened rice to mark renewal, connection, and shared effort. It was a simple act, but one that reminded us how culture lives through use, generosity, and encounter.

The sense that culture moves when it is warmed and activated is shaping many of the changes you’ll see at the JCCC this year. At a moment marked by social fragmentation, ecological uncertainty, and changing patterns of participation, we are becoming more intentional about how cultural practices unfold over time. Rather than concentrating meaning into single dates, we are organizing our work in seasonal arcs that invite return, participation, and continuity.

At this stage, movement will be subtle and uneven. What emerges may feel unfinished or provisional. But like the thaw itself, these shifts alter the conditions for everything that follows. Our hope is that they signal a return of something alive: culture’s capacity to adjust, to listen, and to re-enter relation with the world as it is now.

You’ll see this approach take shape next with our Haru season, and in particular with Hina Matsuri on March 8. In the past, this festival was known as Haru Matsuri or Haru no Matsuri. Going forward, Haru will name the full season of programming we offer across March, April, and May, with Hina Matsuri designating the large spring gathering that opens the season.

Traditionally associated with the wellbeing of children, Hina Matsuri has long been tied to hope and the passage of time. This year, contemporary art, traditional storytelling, and participatory activities will sit alongside long-held practices, creating space to reflect on growing up, being cared for, resisting expectation, and choosing one’s own path.

These changes will be gradual but firm, with the aim of shifting how culture circulates through the Centre - who initiates it, how it is encountered, and how it remains responsive to present conditions.

Hina Matsuri, like Haru Matsuri before it, will carry an atmosphere that is gentle and playful. You might watch a martial arts demonstration, make a doll or a kite, listen to kamishibai, watch community members dance, encounter new work by Nikkei artists, or simply wander with friends and family. Designed to feel both familiar and slightly open-ended, Hina Matsuri is a spring gathering where tradition meets the present.

We hope to see you there.

Water Dropwort Thrives | 芹乃栄

We hope that you have had a relaxing and warm holiday. Our team is back to work and excited for what 2026 will bring. There are many changes afoot at the JCCC, and we have received many requests for more communication so that changes can be shared and understood. This is the first of seventy-two planned messages over the coming year.

January 5 to January 9 is “water dropwort/Japanese parsley thrives”. Japanese parsley (or seri) is one of the seven wild spring herbs that are customarily eaten as part of a rice porridge gruel on January 7th.

It marks the moment in early spring (in Kyoto at least) when fresh green life begins to assert itself after winter. Seri has long been associated with renewal, purification, and everyday nourishment.

The season is meant to point to life returning at ground level, in kitchens and waterways. As I write this, we are being buffeted by a winter storm. There is nothing but white outside, but the JCCC is alive with motion and activity as our team returns from a well-deserved holiday rest.

We are preparing for Oshougatsukai (January), Hina Matsuri (March), and SakuraFest (April). So, I’d like to take this opportunity to explain a little about where our programming is going and what to expect for the rest of 2026.

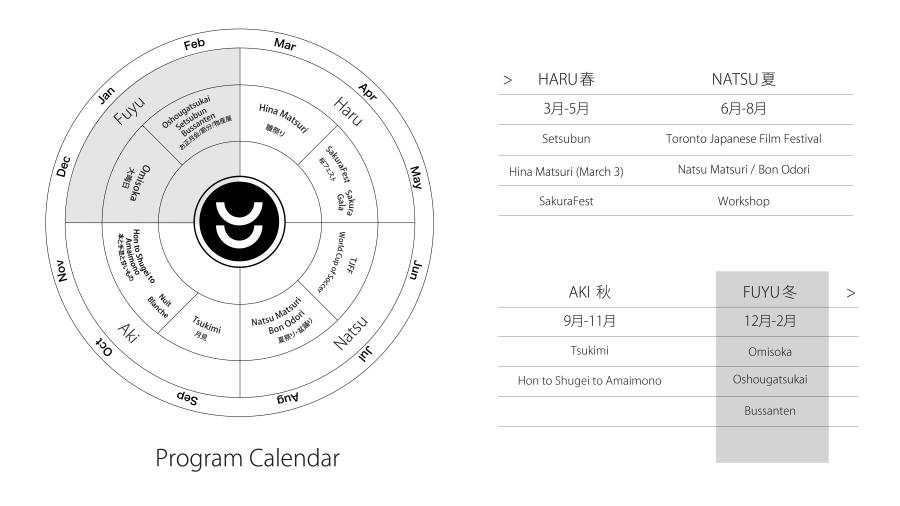

Seasonal Programming

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre is moving to a more explicit focus on seasonality in programming. We believe that seasons offer a simple, shared way of staying connected to culture, community, and the world around us. In many ways, this has always been part of how the Centre operates. Our festivals, food, and traditions already follow the rhythms of the year. We are now being more explicit and intentional about it in how we plan programs and design guest experiences. Seasons help people notice changes in light, weather, and daily life, and encourage presence rather than distraction. In a time of economic uncertainty, climate disruption, and social volatility, these rhythms provide reassurance that change is real but not random. Things are cold right now but it will be warm again. By clearly organizing our work around the seasons, the Centre creates dependable moments people can return to, inviting ongoing engagement and offering a steady sense of continuity, attention, and hope.

Our seasons for programming are based on the climate we experience here in Toronto. Winter includes December, January and February. Spring runs through March, April and May. Summer is June, July, and August. And Autumn brings us through September, October, and November. Each season will have two matsuri, or festivals, that bring the whole community together. One is more traditional and the other more contemporary, but each is an opportunity to gather, to connect, and to celebrate.

Winter: Omisoka/Oshougatsukai and Bussanten (a regional showcase that will kick off in 2027)

Spring: Hina Matsuri (Doll’s Festival/Spring) and SakuraFest (cherry blossoms)

Summer: Toronto Japanese Film Festival and Natsu Matsuri/Bon Odori

Fall: Otsukimi (moon viewing) and Hon to Shugei to Amaimono (books, crafts, and desserts)

There will be other activities that feed into the seasons as well across martial arts, cultural classes, screenings, performances, heritage events, and more.

Whether at one of our long-standing festivals or something new, we look forward to hosting you at the JCCC regardless of the weather outside!

Haru (Mar - May)

Natsu (Jun - Aug)

Aki (Sep - Nov)